Food Packaging Grammar Error

A frozen microwave meal has a grammar error in the instructions. After initial microwaving it says to:

peel film back enough to stir, replace film and cook on HIGH for an additional 1-1 ½ minutes

Do you see the error?

Did you see the error automatically? If it requires conscious analysis to find, then there’s an issue with how your subconscious reads.

The problem is that “enough to stir” is a modifier. It’s nested rather than being part of the list of actions to take.

There is no stirring action specified. The three things you’re told to do are peel, replace and cook. You’re told to peel back the film, then replace the film, without ever stirring.

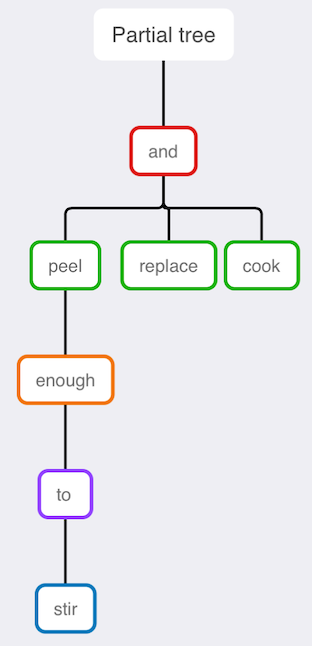

Your subconscious should intuitively parse the text like this tree which clearly shows a list with three actions. The “and” node has three children. The “stir” part is nested further down; it’s not a child of “and”.

Let’s talk about ways people misread this. There are errors that apply in many other situations.

Some people read vaguely. I’ve called this “gist reading”. They see it said something about stirring and they see the order (after peel, before replace). So they assume it probably said to stir without actually reading specifically what it said. Plus stirring is a common instruction, and they often guess what stuff says by what they expect it to say, rather than reading to see what it actually says. Think of this like someone who skims because he doesn’t want to (or doesn’t know how to) read details. It’s pretty easy to imagine someone thinking that stirring was an action they were instructed to do if they only skimmed the text instead of reading it.

Some people read by looking for key words like “peel”, “stir”, “replace” and “cook”. They kind of skip over the details instead of understanding all the words they read.

Related to vague reading, some people don’t consistently pay attention to the logical structure of what they read. In this case, it’s a list of three things conjoined with “and”. But that doesn’t stop people from reading it as four instructions.

If you parse the sentence into chunks but don’t pay attention to connections between chunks, this reading mistake makes sense. It’s reasonable to chunk “enough to stir” separately from “peel film back”. The modifiers on “cook” would also result in additional chunks but that won’t cause the same problem because they don’t have anything that could be confused with a verb.

I think some people read by finding and understanding some individual chunks of text, then they guess how the chunks fit together. They get some clues about relationships from the text, but they also guess stuff that could be figured out by reading. If their guesses are often correct, it might seem like they’re using the skill of reading to get that information but they actually aren’t. Some people pass reading comprehension tests based partly on guessing.

(Related to this, as a child, I remember other people seemed better at hearing whispers than I was. But now I think they were just guessing what was said more than I was willing to. They were also more willing to pretend to hear things they didn’t and hope no problems come up later as a result. They tried harder than I did to avoid socially awkward things like asking someone to repeat what they said. I think most people don’t pay attention to all the words while reading and they think that’s fine. So they also care less about missing a few words when listening. Most people just don’t attach the same importance to words (or numbers) that I do, which is one of the reasons they ask for fewer clarifications. I don’t think the issue was that other kids actually heard more than I did.)

Another error is failure to differentiate finite verbs (the actions or links that lead clauses) from non-finite verbs (gerunds, participles and infinitives, which act like a noun or modifier while still retaining some aspects of a verb). Finite verbs never have the word “to” before them, but many people don’t have that internalized. Finite verbs also never end with “ing”, which a lot more people do have internalized. People are much less likely to misread “stirring” as an action you’re supposed to do than “to stir”. I think that’s because the word “stir”, in isolation, can be a finite verb, while “stirring” never is. But “to stir” never is either, so the pattern there is pretty simple and memorable.

Another issue is that lists require parallelism between the list items. People often get that wrong. But they do partly know it. They might notice that “peel” and “stirring” (gerund) aren’t parallel. But “stir” looks parallel to peel. The word “stir” actually can be a finite verb just like “peel”. However, when you see “to stir” then, whether the “to” is a preposition or particle, “stir” is an infinitive, not a regular verb like “peel”. In English, it’s somewhat uncommon for an adjacent word to be so important, so people get used to looking at single words in isolation. This also sometimes leads to people missing a “not”. But the word “not” is almost always important so it stands out for some people. “To” is often closer to a filler word that isn’t very important, so some people get in the habit of ignoring it.

Also, I think many people don’t quite know that, basically, a chunk of English text can only do one thing. “Stir” can’t serve both as a modifier and also a list item. It can’t go in two different places in the grammar tree. I think many people are so used to considering chunks out of context that they can use “stir” in their mind in two different ways at two different times without realizing the contradiction. (There are some exceptions where a word can be represented by two tree nodes, e.g. with implied words or relative pronouns.)

For most people, understanding the shape and structure of the grammar tree is something they could only do by making a tree diagram and putting in conscious effort and analysis. To be great at reading, you need your subconscious to deal with this kind of thing accurately. It’s a fairly simple case. Philosophers and other intellectuals write much more complex or convoluted sentences. I think this is a pretty typical example of one of the kinds of things that can set apart the really smart, logical people from others. They win their debates and make way fewer errors because their subconscious can correctly handle lists of three things and nested modifiers. Most people can’t reliably and intuitively get that right, so they’re at a disadvantage.

The text on food packages from large brands at major grocery stores is created by a team of people. It wasn’t just one author who screwed this up. Other people approved it too. A bunch of people at the company were blind to the issue. And I think most customers are blind to the error, too.

All the errors discussed are possible to make when analyzing consciously, but are more common errors for people’s subconscious analysis. People who spend five minutes trying to figure out what it says will make way fewer errors than people who just casually read it once. If you want to be a great thinker, it really helps if your subconscious can catch issues like this on your first reading when you don’t know there’s an issue and aren’t really trying. Using significant conscious effort for all your important reading would take too much effort, leaving you less energy for consciously analyzing the hard or controversial parts. Great thinkers usually only need to do five minutes of conscious analysis for harder cases, not cases like this.

By the way, I don’t actually have a clear answer for whether “enough to stir” modifies “peel” or “back”. Is it telling you how far to peel or how far back? This doesn’t significantly effect the meaning which makes it hard to tell. My current best theory is that English has some common grammatical ambiguities that have never been fixed because they don’t cause enough trouble for people to care. Or put another way, English relies on content and meaning to resolve some ambiguities rather than having a fully unambiguous grammar. When the content or meaning of two options are very similar or identical, then we may not be able to resolve an ambiguity. But it doesn’t matter much because it won’t lead to misunderstandings about what the sentence means. The times we can’t resolve these ambiguities are the same times they don’t affect the meaning much and therefore won’t cause misunderstandings.

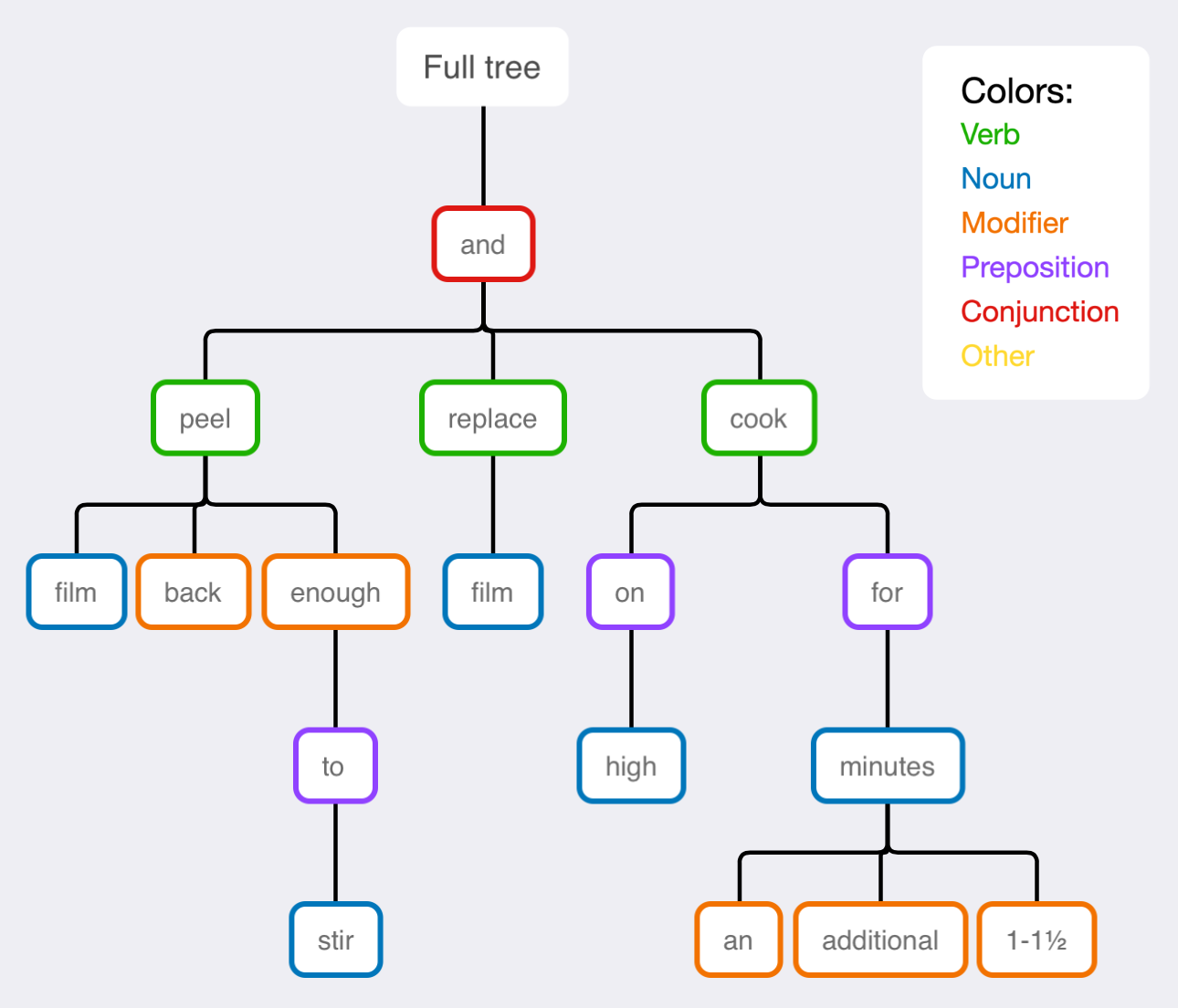

I’ll close by sharing my grammar tree for the full sentence:

EDIT 2023-04-15: I wrote a followup post with comments on this post.